“[The world of] Islam has fought against the west and colonialism more than all Asia and Africa. These two old enemies [of Islam] have inflicted serious wounds on its body and soul. And it bears alone the hatred of these enemies, which have struck it more frightfully than they have others. And although I do not feel the same way towards it as you, I would like to emphasize, more than you do yourself, your remark that Islam harbours, more than any other social powers of ideological alternatives in the third world (or, with your permission, the Near and Middle-East), both an anti colonialist capacity and anti-western character…”

– Frantz Fanon, “Letter to Ali Shariati”

For the longest time neither Fanon nor Shariati would have recognized non-Black Muslims in the United States. Non-Black middle-class Muslims had become just like the white middle class: absorbed in cars, big homes, careers, self-pleasure, and other pathetic goals. They worshipped and prayed to the only God standing: U.S. Empire and the U.S. dollar. To expect anything from this group was to find yourself in the maze of self-deception.

The non-Black Muslim middle class in the United States did not have to fight for its place. That path was cleared by the Black movement and the Black middle class. Some had even come during the Civil Rights Movement, and instead of throwing themselves into the struggle, they simply went along their way, preparing for a promised future. Today the non-Black Muslim middle class gets to enjoy the fruits of the Black movement. This does not mean the non-Black Muslim middle class did not face obstacles, did not huddle in homes when they first came, but they never had to stage giant marches, sit ins, or form an armed struggle organization to simply live in this country. The formation of the non-Black Muslim middle class was a process of abandoning the home country, transforming oneself from Muhammad to Moe, and ultimately bowing down to U.S. Empire.

Meanwhile the Muslim proletariat was submerged due to 9-11, its small size, the general lack of class struggle, its own anti-Blackness, its belief in the American Dream, its grappling with the new reality of this country, and the hegemony of the Muslim middle class. Without a Muslim proletariat on the move, politics became the dead end of policy and the law.

Today, the meaning of struggles involving non-Black Muslims has finally started to emerge thanks to the clarity provided by Somali Muslims in Minneapolis in the George Floyd Uprising. Most of the history is not radical, but the failures of reformism are often the ground upon which radical politics and actions grow. The post 1960s history begins with student solidarity activism around the Iranian revolution in the 1980s, protests against the Gulf Wars in 1990 and 2003, Palestine Solidarity during the Second Intifada, the Boycott Divest and Sanction campaign, and finally protests at airports against the Muslim Ban. While struggles involving non-Black Muslims have been legalistic, tame, and hardly radical, it was the Muslim ban that introduced a crack into what is possible, followed by the Minneapolis uprising which completely broke away from the law and reformism. Using the uprising as a lens to view the post-9-11 world, everything has begun to look a little different. This is not the end of this story, but the documentation of the dawn of a new species. At the center of this story are Black Somali Muslims in Minneapolis and the particular intersection of Blackness, class composition, arrivants,¹ and Islam, resulting in an explosive mixture.

Good Muslim, Bad Muslim

Muslims did not get to choose the political terrain the fight would occur. Since 9-11 the polarization has been between so called good Muslims and bad Muslims. The Muslim Ban in 2017 once again created the good and bad Muslim. These good Muslims had fought for the U.S. Empire, some were ‘hard workers’, and some professed loyalty to the "American Dream." All were telling other Americans that they were not radicals and certainly not terrorists. They were the “good Muslims.” This logic goes back to 9-11 where the only imagination of Muslims acceptable to the public is the equivalent of an Uncle Tom—an Uncle Muhammad. And so the performance began. In other words, the polarization created by 9-11 forced every Muslim to be either a terrorist or an Uncle Muhammad. The space to be a revolutionary and be Muslim evaporated not only in the mainstream, but also in the left.

The caricature of the Bad Muslim is of course Osama Bin Laden–the baddest Muslim of them all. With this polarization, Muslims were not able to find an alternative subjectivity to cohere around. It is here where the tradition of radical Black Muslims can break this polarization, creating a much needed three-way fight amongst Muslims. The struggle of Somali Muslims is precisely this third pole, which finally begins to break the polarization of good Muslim, bad Muslim. Although Somali Muslims have not been immune to playing the game, their actions in the uprising point towards an entirely different pole, through the intersection of Islam and the Black Radical Tradition, reviving the particular history of Black Muslims in the United States. This is a process that has just begun and is fragile.

The Actual Muslim Problem

Non-Black Muslims face several problems in the United States: a) whether as settlers, arrivants, immigrants, or aliens they are structurally situated as an anti-Black subject b) they are a demographic minority reliant on the solidarity of others, and without radical politics, they will always cozy up to the rulers; c) they do not have a rich history of struggle in the United States, d) they do not take up much space in the imagination of liberation, and e) their class composition is framed around the idea of Islam which tends to hinder class struggle. All of this is rooted in the material facts of Muslim life in the United States.

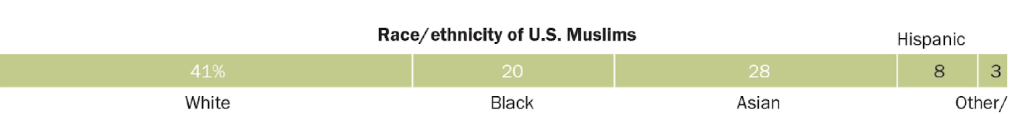

Source: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/

Muslims make up about 1.1% of the U.S. population for a total of 3.45 million Muslims as of 2017. Muslims are fractured before they even enter the United States. Some examples: Muslims from India are not really refugees, while Muslims from Somalia or Syria are; Muslims who speak English have huge advantages over those who do not; and Muslims from middle class backgrounds and with college degrees are able to establish themselves fairly quickly in contrast to those who come from proletarian class positions from their home country. At the same time, understanding how racialization takes these fractures and glues them together into a Muslim population is a demonstration of how Islamophobia works. Meaning that regardless of these differences, Muslims are seen as a uniform community by many Americans. However, the bulk of state repression around terrorism tends to fall on Muslims from the Middle East, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Somalia. What all this crisscrossing of bonds and fractures means can only be revealed in the course of the class struggle. We see some glimmers of this fracturing in the way that masjids are divided by nationality. For all the discussion of a larger Muslim community, Muslims reveal very clear divisions by where they pray in mosques, which often map onto class and nationality.

Income differences are vast amongst Muslims. Indian Americans have the highest median income out of any group in the country at $127,000 with Somalis with one of the lowest at $20,600 and Iraqis with $32,800. The average household in the United States has a median income of $63,000. Commonalities stretching across class tend to be weaker in terms of political struggle. This doesn’t mean there are no cultural and religious overlaps between such diverse incomes and class positions, but their different structural relationships to racial capitalism are not comparable. As class struggle intensifies these differences reveal themselves to be particularly important.

Income and education are not a precise way to look at class structure, but it can give a rough sketch of what that looks like. While much has been made of the arrivant class composition of Muslims, it appears that at least around income, they more or less match up with the rest of U.S. society. Around higher education, U.S. born Muslims are doing worse than the U.S. general public, another sign not only of a proletariat, but also that the class structure of U.S. capitalism is imposing itself on Muslims.

Source: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/

Source: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/

As a small religious group in this country, non-Black Muslims are an easy scapegoat for many of this country’s problems. In the United States, non-Black Muslims do not have a tradition of rioting, armed self-defense, strikes, blockades or occupations. In this sense they are a community without a tradition of militancy and an easy target for the right.

Muslims are both invisible and hyper-visible. Muslims often complain that no one cares about the oppression of Muslim oppression. The riddle of invisibility is very simple for non-white groups in this country. Those who riot, blockade, strike, occupy, and conduct armed self-defense are not invisible. Small minorities who stick to voting will always be invisible because on the logic of the vote, by definition you are a small-time player, hardly visible to the sea of whites, Blacks, and Latinx folks that compromise the main groups of voters in this country. You can only be visible by extra-parliamentary means. At the same time, small demographic groups cannot do this on their own, and must figure out how militant actions take place as part of a broader struggle. Isolated militancy is a quick way to land in prison. Alliances with the rest of the proletariat will have to be made. The answer to invisibility is a combination of militancy and alliances.

Non-Black proletarian Muslims in the United States are unlikely to develop a radical politics on their own. Their trajectory will be marked by how larger movements and demographics relate to them. Most importantly movements will need to educate them, make space for them, and foster a revolutionary politics that can speak to both the specific forms of oppression that non-Black Muslims face at the same time maintain a firm stance on Black liberation. This is not popular to say these days because it can be seen as denying the agency of non-Black Muslims and putting the burden of education on Black movements. The agency-burden dichotomy masks its own form of liberalism, which can only be resolved from a revolutionary vantage point.

Genealogy

The argument I am making about Somali Muslims is not unprecedented, but part of a revolutionary tradition such as W.E.B. Du Bois’s Chapter 4 in Black Reconstruction, C.L.R. James’s Historical Development of the Negro in the United States, Claudia Jones’s An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman, Eldridge Cleaver’s On the Ideology of the Black Panther Party, Muhammad Ahmad’s World Black Revolution, Malcolm X’s The Black Revolution. This tradition explains the most dynamic elements of class struggle inseparable from the development of racial capitalism.

Muslims have no language to communicate with the left at the current moment. The language has been dominated either by terrorism or liberalism, creating a purgatory for revolutionary Muslims. Malcolm X argued that Islam was a private matter, instead focusing on how it was being Black which made Black people catch hell. This point made a lot of sense, but today, some nuances might be in order, considering the wars waged in the Middle East, Islamophobia across Europe, the Uyger camps in China, and of course Islamophobia and Orientalism in the United States.

The left is the place where outcasts and freaks go to, but there has always been a necessary battle in making the claim that such and such group is radical and important. Black people, waged and unwaged women, and Queers, have all had to fight to be recognized in the left, to have their oppressions taken seriously, and so that they are not just victims, but revolutionary agents, capable of changing the world. The project for Muslims in the context of this country has only just begun.

To think of Muslims and Islam on such terms is difficult for many on the left. But another way to think about it is to realize that the same story and contradiction exists within communism. There is nothing inherently emancipatory about communism. The experiences of Russia, China, and Cuba are one set of proofs. Another is that Black people, women, and Queers would have had to fight for their place and legitimacy in the movement. Even Black liberation has succumbed to this dynamic where Black women had to fight for a more feminist understanding of Black liberation in the 20th century. The same tensions certainly apply to Muslims. Islam is a contested political field no different than communism or anarchism.

Muslims in the Black Radical Tradition

Non-Black Muslims can only find a way of life by turning to a particular tradition of Black Muslims in term of a) understanding race, b) how to live, and c) how to fight. This tradition is the unity of Islam and the Black Radical Tradition.

What is the relationship between the Black Radical Tradition and Islam? There have been six major phases of Islam and the Black Radical Tradition. The first were the Black Muslims who were forcibly brought to the so called New World and rebelled against slavery across the Black Atlantic. The second is inaugurated by Noble Drew Ali, founder of the Moorish Science Temple of America, acting as a bridge between Islam and an analysis of race. The third was the Nation of Islam which, Malcolm X ushered in at a mass level. The fourth were the currents in the Black Panther Party, Black Liberation Army, and Republic of New Afrika that converted to Islam. The fifth were Black Muslims in prison. The sixth are the Somali Muslims in Minneapolis. Another way to say it is that there would be no Islam in Amerikkka without Black Muslims.

This tradition is not without tensions. Many Muslims view the Nation of Islam as heretical and not legitimate. This is inseparable from the anti-Blackness of many Muslims who cannot see how the NOI was a unique and necessary innovation for Islam which accounted for race. And how Somali Muslims will impact Islam is still speculation, since Muslims themselves are segregated and often anti-Black, and may well just ignore what occurred in Minneapolis.

With the murder of Malcolm X and the defeat of Black revolutionaries in the 1970s, the radical tradition of Black Muslims went quiet for several decades. In the meantime, millions of non-Black Muslims came to the United States. In the absence of such a tradition to guide non-Black Muslims in the United States, they have been a lost people, wandering this land, a people without purpose other than to work and reproduce.

But then the azan was made in Minneapolis, with the fires of the 3rd Precinct. Holy ground found its way to Turtle Island. This was the signal to the entire proletariat on Turtle Island, that the hour had come to wage a battle against the forces of law and order. The proletariat did not disappoint. The intersection of Islam, class, police violence, and Blackness detonated a national and international uprising. Equally important, the merging of Islam and the Black Radical Tradition might provide a solution the impasse of a liberal pro-capitalist Islam and the Salafi and Wahabist trends which have played such a defining role. In other words, for Islam to become relevant in the worldly affairs of hunger, homelessness, and inequality, it must merge with Black struggles.

The Making of the Somali Muslim Proletariat

Somali Muslims started coming in large numbers in the 1990s, after the Somali civil war. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis found themselves in refugee camps and some were able to come to the U.S. as part of a refugee resettlement program. Somali Muslims came with little if anything, and were dependent on state social services to survive. When they did get jobs, a substantial portion of their income went back home. Many Somali men could not find jobs or could only find low-paying jobs, which meant they became part of the working poor stuck in low waged jobs and welfare. Ultimately they and their children became trapped in the proletarian class position.

Minnesota and specifically Minneapolis became the major destination for Somalis. Today there are 57,000 Somalis in the Minnesota area. In comparison to other states, Minnesota is structurally more social democratic in terms of funding for social services. And yet a tendency toward social democracy did not prevent an uprising from happening. Minneapolis has some of the most severe racial inequalities in the country. In the state, the median Black family earns $38,000 a year while for white families it is $84,500. The Black poverty rate was 25.4% which is over four times the white poverty rate of 5.9%. For comparison the national Black poverty rate is 22%. Things have not been good for Black people in Minneapolis for some time.

Minneapolis and the state of Minnesota imagine themselves as progressive and good liberals, all culminating in the comical slogan of “Minnesota Nice.” This imagination is a creation of white civil society always imagining a positive relationship with Black people. Although this self-perception has been changing in the last few years because of the pandemic, economic stagnation, and Black Lives Matter, on average, whites tend to have a naïve sense of their relationship with Black people.

At the same time, Somalis have acknowledged the important role of state and federal financial assistance in surviving, but have also noticed its impact on gender relations in the family. There seems to be agreement amongst Somali women that access to welfare state resources has improved their position, that the system had empowered them by designating them as heads of households. In contrast, Somali men tend to see the United States as a country where women dominate.

The welfare program in Minneapolis known as Family Investment Program is a classic neoliberal twist on welfare. Derived from Clinton’s so called ending of welfare, it is meant to push poor proletarians off welfare and into the workforce. If there is anything that this welfare scheme does, it is to trap proletarians into specific segments of the labor market. You have five years to become a viable worker. If you don’t you are out of luck and the state stops sending you a check.

Like Puerto Rican migration in the post World War II, which slotted them as workers in a declining labor market, Somalis have found themselves to be trapped in a particular segment of the capitalist labor system, namely, that assigned to low waged workers. For the last several decades the economic picture in this country has been that of a stagnating capitalism: while jobs can be found, many of them are in low waged service sectors, which is exactly where Somali Muslims find themselves today. The other factors are skills and education level of parents. With limited education and English language skills, Somalis are tracked to low wage jobs such as janitors, factory and assembly line workers. The jilbaab also becomes a barrier, sometimes due to racism and at other times due to workplace safety, particularly in factories, forcing many Somali women out of the labor market.

The class structure of the Somali community is particularly important. There is no Somali bourgeoisie in the USA. There is a tiny Somali middle class barely hanging on. In one sense, the Somali Muslims community is almost entirely proletarian. In contrast to the stereotype of arrivants as middle class exiles, Somalis are as proletarian as you can get. However, there is a developing Somali political class tied to the Democratic Party, with Ilhan Omhar as the signature representative.

Somali immigrants have many of the same romantic expectations of the United States that other immigrants do. But like earlier generations of Caribbean immigrants who had known little day to day racial oppression in the Caribbean for being Black, their encounter with the United States was both a shock and a reason for mobilization. Nor have Somalis and African Americans been immune to mutual practices of self-distancing from one another: Somali-Americans from being seen as African Americans and vice versa. But over time the younger generation has learned that this distancing is irrelevant, because to the forces of authority, and to whites, they are seen as Black.

Somali proletarians are involved in gangs, sex trafficking, and al-Shabaab. We do not know what relationship these activities had with the riot. But it would be naïve to say that some of the people involved in these harmful behaviors did not participate in the riots. While we need to be careful in seeing riots merely as criminal activity, at the same time, as sociologists have noticed, there is a structure of participation in riots. The first set of rioters are often young people who set things in motion. Then gangs and other illegal elements enter the riots. Finally more stable working class layers participate.

Is the uprising a refutation of those practices or is there a continuity? In fact they are both connected. Fanon argued that the dangerous classes commit immense violence upon each other because they are not able to attack their oppressor. According to Fanon, the solution was turning this violence towards the oppressor. Only through this process could a new species be forged. This line of thought, in one single blow, destroys a whole set of liberal, progressive, and conservative solutions to the violence amongst proletarians.

The social and political realities that Somali Muslims face result in a highly political and mobilized community. The uprising in Minneapolis was not random, but part of a broader cycle of struggle which can be traced back several years. While no organization caused the uprising to occur, the uprising was not as divorced from previous struggles as I have originally estimated. Below is a list of some of the struggles Somali Muslims have been involved in:

-On December 2015, 200 Somali Muslim employees at Cargill Meat process plant in Fort Morgan, Colorado walked off their job for three days, because they were not allowed to take breaks to pray. Interestingly Cargill is headquartered in Minnetonka, Minneapolis, suburb of Minneapolis.

-In 2016, Somali rapper K’naan faced protests from other Somalis while hosting a block party. They were protesting K’naan latest project, a HBO series, described as a drama about jihadi recruit in Minnesota. Somali protestors were angry that one of their own was depicting the Somali community as a breeding ground for terrorism. The protest turned into a small confrontation with the police where they were pepper sprayed.

-Sixty percent of Amazon’s 3,000 workers in the Minneapolis region are East African. One of the workers Khadra Ibrahin says “Breaks make our rate slow down and then we’d be at risk of getting fired, and so most of the time we choose prayer over bathroom, and have learned to balance our bodily needs”. On December 14, 2018, Khadra Ibrahin was part of a group of Somali workers who staged a walkout at an Amazon warehouse. Her experience as a proletarian is epic and reflective. She has worked off the coast of Alaska in a fishing boat, cleaned Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, and as a packager in a Target warehouse, before working at Amazon. This migratory trail is reminiscent of workers in the old Industrial Workers of the World.

-Somali Muslims were at the frontlines fighting corporate America’s mishandling of the pandemic. In a Pilgrim’s Pride meat plant in Cold Spring, Minnesota, Somali workers found themselves in a plant with little protection for workers from COVID-19. As of June 2020, this plant had 200 COVID cases. About 100 workers staged a walkout and teamed up with residents in the community to protest outside of the plant. The UFCW negotiated a $300 bonus in March for workers, its website says nothing about working conditions and safety regarding the pandemic. The role of the UFCW is not clear in the walkout, since no journalistic article mentions them.

How these actions relate to the Minneapolis uprising is unclear, but we do not need to create a wall between workers organizing and the uprising. Some speculation might be helpful at this point. We know that riots in the 1960s tell us that plenty of ‘workers’ participated in riots. In the Louisville struggles, I had assumed that class composition divided the rioters form workplaces, but at least in the case of Minneapolis, it might be the same people who were involved in the riot were also involved in workplace struggles.

This list is not exhaustive, but meant to outline the efforts of Somali Muslims fight against Islamophobia, anti-Blackness, police violence, and inequality. And that their ability to fight is not reducible to any single reason of race, religion, or class, but reflects the complex articulation of how different forms of oppression and identity come together in moments of struggle. This list hopefully sheds light on how a proletariat is being made through the processes of struggle itself. It also hopes to show that proletarians are finding ways to coordinate their shared misery.

Has a New Muslim Arrived?

Minneapolis is just one giant prison. Many who propose defund, imagine prisons to be a fixed spatial geography in prisons, jails, and police stations, but what happens when an entire city is a giant prison. In this situation the most rational thing Somali Muslims and other proletarians could do is to burn the prison down which was the city, which to an outsider looks like crazy Black proletarians burning their own neighborhoods down. This is why C.L.R. James in Black Jacobins wrote the most powerful explanation of fire, the riot, and destruction ever written:

"The slaves destroyed tirelessly. Like the peasants in the Jacquerie or the Luddite wreckers, they were seeking their salvation in the most obvious way, the destruction of what they knew was the cause of their sufferings; and if they destroyed much it was because they had suffered much. They knew that as long as these plantations stood, their lot would be to labour on them until they dropped. The only thing was to destroy them."

For those who do not understand what James is saying and what the slaves did, they simply cannot grasp what prison or capitalism are.

Post 9-11 surveillance against Somali Muslims has been particularly severe ranging from surveillance in masjids, schools, and social media accounts. Young Somalis found themselves surrounded by a carceral apparatus everywhere they looked. In 2014 the Obama administration launched Countering Violent Extremism, a Muslim surveillance program, with Minneapolis as one of the pilot cities. It was marketed as “a health and human services program” which is a precursor of how post-pandemic surveillance and policing might appear.

The surveillance of Somali Muslims is inseparable from them being Black, Muslim, and foreigners to the United States. Somali Muslims faced not only the Minneapolis Police Department but the full force of the entire U.S. intelligence apparatus because they were always suspected of harboring terrorists.

Recently one Arab Muslim from the Minneapolis was arrested. According to the U.S. Attorney’s Office, on May 28, 2020 they were an accessory to destroy by means of fire, Gordon Parks High School. This might seem like a classic case of picking a target that does not make sense, but the history of schooling and surveillance is proof that the school is more prison than a site of learning. It was by participating in a Black led uprising that this Arab Muslim has opened the door to non-Black and Black Muslims forging a different vision of Islam and Muslims.

It seems like with the Minneapolis Uprising, we can finally ask ourselves the question that no one has been willing to ask. Is there a new type of Muslim that has arrived in the United States?

The events in Minneapolis may signal the emergence of a Fanonist new species: “Decolonization is quite simply the replacing of a certain ‘species’ of men by another ‘species’ of men. Without any period of transition, there is a total, complete, and absolute substitution.” It is precisely because of the violence used in the uprising that this is even possible. As Fanon reminds us “decolonization is always a violent phenomenon”. The burning of the 3rd precinct was the penultimate decolonial act, no longer metaphor, but a transformative act.

This species of Muslim will be attacked by all of society. The first line of attack will be the Imams in the masjids. Imams across the country are collaborators with the state, giving them names, preaching pro-capitalist and pro-imperialist messages. They are the frontline of architects of those who worship the U.S. State and the Benjamins. The second line will be the Muslim middle class who will look at these new species as a threat to their ability to assimilate into racial capitalism. They will play a role no different than the Black middle class. The third line of attack will come from the social democratic left. This portion of the left can only understand Muslims as victims, or as a variant of the Good Muslims. It is obvious state repression in all kinds of manner will also be a factor, but that is obvious, and needs little further explanation.

The new species is the product of class struggle. For this species of Muslims to flourish, this requires not only intensification, but the defeat of the Good Muslim, Bad Muslim polarization. This species will have to sit on the intersection of Black and non-Black Muslims, but ultimately be led by Black Muslims. It will take nothing less than an anthropological revolution which has begun with Minneapolis. The question of the coming years will be: can non-Black Muslims keep up with their fellow Black Muslims will be the question in the upcoming years?

Conclusion

For those of us radicalized because of 9-11, being a Muslim revolutionary has been nothing but disappointing. For almost two decades we have watched the Muslim middle class lead an oppressed people to its doom. For many years we looked for signs of revolutionary potential for Muslims and could find nothing. Palestine Solidarity which was the most hopeful political struggle, revealed itself to be nothing more than cultural events, lectures, and symbolic protests. Activists would discuss the Intifada, Frantz Fanon, and Leila Khaled but what we did in the United States had nothing to do with what was happening overseas or the revolutionary past which we imagined ourselves to be a part of. Palestinians threw rocks and picked up the gun, but in the United States we conducted peaceful marches, weak boycotts, and held conferences. It is this disconnect which forces many of us to feel a deep sense of failure. Palestine, Iraq, Sudan, to name some places where Muslims have fought bravely, were matched by the inverse in the United States, that is, until the uprising in Minneapolis.

Whether this development will flourish is not clear. But for the first time since the days of Malcolm X, something more about Muslims can be said other than “what a bunch of miserable victims.” To no surprise the spearhead of this revival are Black Muslims and specifically Somali Muslims. A series of questions are left open: Will non-Black Muslims follow the lead of Somali Muslims, or will they reveal themselves to be thorough and dedicated anti-Black racists? Can a Muslim proletariat emerge with its own set of politics? Can this Muslim proletariat intersect with the struggles of other proletarians? Will Somali Muslims change our understanding of Islam when it comes to liberation? Will the struggles of Muslims take on a sustained militancy which can finally free the Muslim world of U.S. imperialism?

While Muslims will never be a demographic majority in this country, they are no longer trapped by their specific circumstances. The brave actions of Somali Muslims have opened the door to something else. Exactly what that is, Muslim proletarians must figure out.